House for sale in France

Early retirement gave us the opportunity to pursue our dream of living in France. Tipped off by a French friend I met in Kuala Lumpur, we started our search for somewhere to live in the lovely city of Toulouse. We would drive into the countryside exploring the surrounding areas and, to cut the story short, after 3 months we started renting a cottage near the town of Lavaur. Just over a year later we moved into the house which has been our home for 15 years. Being nature lovers we had found paradise!

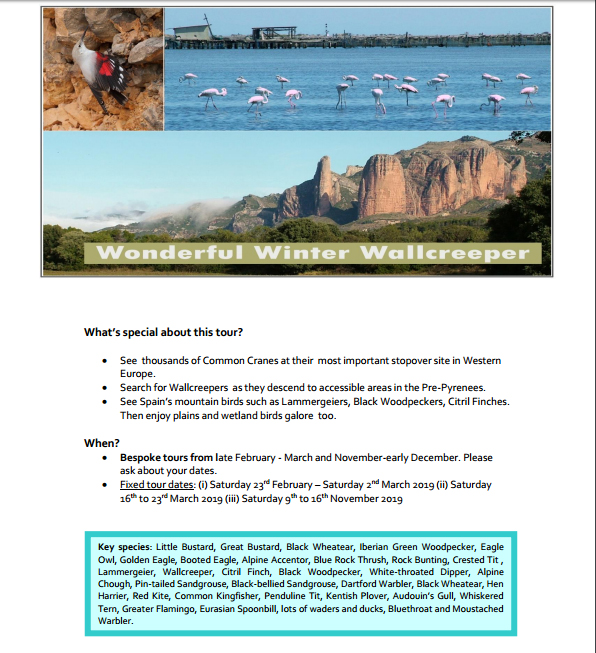

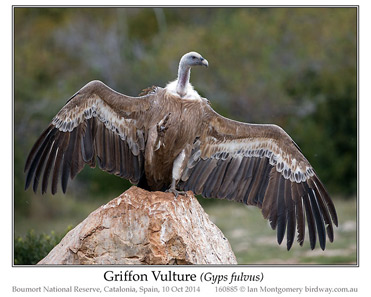

Facing due south, situated at just over 300m, we have a magnificent view over the Agout valley and on clear days on to the Pyrenees. We have almost 1ha of land, with mature oaks and pine trees, a natural habitat for lots of wildlife. Roe deer and wild boar pass through, and we’ve also enjoyed pine martens and red squirrels, bats, lots of birds and wild flowers, particularly wild orchids. It’s a delight to sit on the large deck in spring and listen to the cuckoo, and then a bit later to hear that the Golden Orioles have arrived. Hen Harriers, buzzards, Short-toed Eagles and kites often fly overhead, and we even saw Griffon Vultures one time. Nuthatches visit the bird tables in winter ,along with the usual robins, tits, etc. Black Redstarts return in the spring and are a joy to watch, and we have had an occasional Hoopoe.

Now it is time for us to embark on another adventure and we are selling En Mimosa. Conveniently situated in a small community, only 6 kms from the nearest villages with shops, schools, market, Mairie and railway station, for easy access to Toulouse. With lots of activities locally – golf, riding, etc., walks in the woods straight from the house, it is an ideal holiday location.

Centrally heated accommodation (170 m2) comprises 4 bedrooms, two en-suite, bathroom, fitted kitchen, large double height lounge/diner with wood-burning stove (self-sufficient in wood) and mezzanine. There are covered north and south facing terraces, each room has access to the outside, plus the large deck for entertaining or just sitting soaking up the tranquility and beauty of the surroundings. We also have a full sized basement (150m2) with windows at one end, suitable as a studio, workshop or garage.

Mary Davis

For further information please contact us as follows:-

En Mimosa

Lacapelle

81220 Damiatte

France

+33 563421528

Clive.gaitt@sfr.fr

Mary.davis@sfr.fr

* Steve’s note: Mary and Clive are long-standing clients of Birding In Spain, and we wish them all the best in their new life venture.